One of the fun things about being a soap maker is that it’s the most mundane of products. Soap, the bar of soap, is an everyday thing. What it is for us, how we use it, we hardly think about it. And yet, it’s a product of intimacy, of the body, of hygiene and therefore of the backstage… And simultaneously, its use, its representations related to hygiene are always social, cultural and historical.

Yes, you understand that with us, soap is the alpha and the omega (What? No, we are not excessive!). In fact, if we retrace its history, we see that what is played out between you and your little piece of soap every day is the history of humanity. That alone, yeah!

Already because soap would have been discovered in prehistoric times. Perhaps even in the Périgord by a Cro-Magnon cooking a small leg of lamb in rainy weather: fat, ash and water, the trinity of the soap maker! This is what Roger Leblanc* imagines in his book. Because if we don’t really know how things worked out, prehistorians did find substances similar to soap during their excavations. However, to find some more tangible traces, we have to teleport to Mesopotamia, 2800 years before Christ.

It is thus on a Sumerian tablet in the region of Babylon that we find the first handwritten indications of soap making. The Sumerians evoke more precisely a kind of soap paste, composed of water, alkali and cassia oil. It is not really a soap reserved for hygiene. It is used to clean and treat wool and cotton.

It is thus on a Sumerian tablet in the region of Babylon that we find the first handwritten indications of soap making. The Sumerians evoke more precisely a kind of soap paste, composed of water, alkali and cassia oil. It is not really a soap reserved for hygiene. It is used to clean and treat wool and cotton.

We find other mentions of soap in the writings of Pliny the Elder. He mentions the existence of Cepo galliarum in Gaul. It was a mixture of tallow, lard and edible oils mixed with ashes. If it is used for body hygiene, it is also used for hair, especially to color it.

Strangely enough, the Romans, like the Greeks, known for their very fine body care traditions, did not use soap until later. They used to wash themselves by « abrasion »: some used powders to rub their bodies before coating themselves with oil, others coated themselves with oil before removing it by rubbing a strigile, a kind of scraper. It was not until the 2nd century that the Greek physician Galen recommended the use of soap for both therapeutic and hygienic purposes.

Plant powders, clays, minerals as well as oils, steam or even frictions and wraps are juxtaposed, precede or complete the use of products strongly resembling the soaps we know today.

If the techniques of the body differ according to places and times, they are universal. Soap has a predominant place in them. Some of these legendary soaps are still made.

On the African continent, it is the black soap that is described in the literature. Based on palm oil, shea butter, cocoa butter mixed with ashes of plantain peels, palm and/or banana leaves, cocoa kernels, there is a multitude of recipes. It seems that the Yoruba, originally from what is now Ghana, were the first producers and allowed its diffusion first in West Africa and then throughout the continent. This solid black soap would be the ancestor of the black soap paste of North Africa. It is still a famous soap.

Three other solid soaps are legendary: the soap of Aleppo, the soap of Castile and the soap of Marseille. The first one is precisely detailed in the most famous Arab medical treatise of the Middle Ages, TheKitab al-Mansouri fi al-Tib (The book on medicine dedicated to Al Mansur). Dedicated to the governor of present-day Iran, it was written by Al-Razi, a Persian physician, naturalist, philosopher and alchemist. In this work, copper cauldrons are described in which a mixture of olive oil, soda and laurel ashes and water are boiled. The soap blocks are then dried for 12 months in the sun. It is from the Arabic language that the term alkali, Al-qali, comes.

The dense relations between the Arab world and the south of Europe allow the massive diffusion of Aleppo soap and its codified manufacturing techniques. Historical upheavals slowed down this trade and encouraged the main olive oil producing areas in Europe to produce their own soaps: Italy, Spain, southern France, Greece.

This is the quasi-official appearance of olive oil soap, which will gradually become Castile soap. This soap certainly already existed, as there were soaps made from animal fats in northern Europe. The Castile soap has the particularity that it is made cold and that it contains only olive oil, no other fat. Very low foaming but very soft, with a light smell, it is very popular. The so-called Marseille soap is also developing. It is made at high temperatures, with an excess of soda, and is manufactured throughout southern Europe.

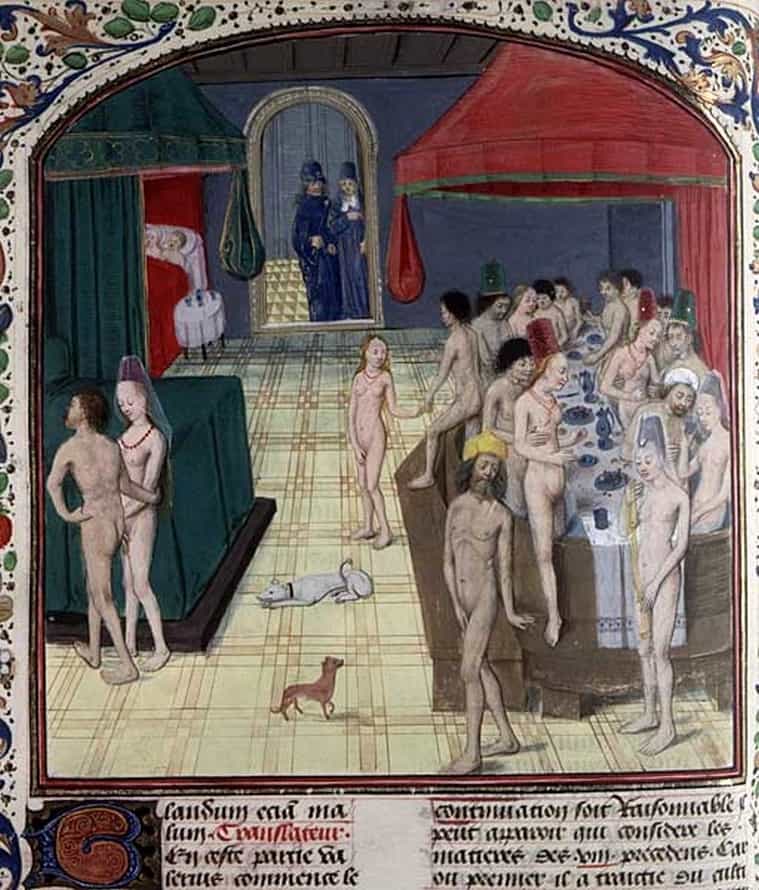

The Middle Ages were the time of the « étuves », public baths accessible to the wealthy. For the others, there are still the waterways. And people hurried to them. Contrary to popular belief, the Middle Ages were a time of hygiene and body care.

In 1371, documents attest to the official presence of a soap maker in Marseille. However, the guilds of soap makers had been established throughout the country for a long time. A text drawn up by Charlemagne, as early as 800 A.D., requires that soap manufacturers be properly established throughout the territory and, in passing, that 2/3 of the production be reserved for him. Because soap remains quite expensive. Moreover, in public baths, it is possible to use soapwort flowers if one cannot afford a piece of soap.

The end of the Middle Ages was quite different. It was considered that water carried miasmas. This is the « theory of humours ». And, in times of plague, this belief had a certain effect. It is a partly true belief. Streets act as public latrines. Animal, human and chemical pollution all flow into the waters. Tannic extracts poured by the dyers, blacks from the blacksmiths’ boilers, etc. are mixed with human fluids and waste. The people stop bathing, they wash with moderation, preferably without water. They prefer alcohols, most often perfumed. They rub it on themselves and then powder and perfume themselves, a lot. During the Renaissance, the dirt became a natural protection, a barrier to the infections that abounded.

It was in the 18th century that water regained its purifying status. Baths multiplied until the arrival of the hygienists in the

19th century. Soap continued its evolution, discreetly.

Its production has been industrialized. Alessandro Giraudo* recalls that in 1786, in Marseille, 49 soap factories and their 600 workers produced 76 000 tons of soap. To meet the needs, convicts could even be « loaned » by the Arsenal of the galleys to increase the workforce. Chemistry also played its role. First in 1791 with Nicolas Leblanc who patented a process for manufacturing soda on a large scale. It worked, but it was expensive and polluting. Etienne Solvay then improved the process. At the same time, the invention of electricity and the installation of large factories increased production possibilities.

This is the golden age of soap making. Little by little, soap, heavily taxed until very late in the 19th century, became cheaper. It was produced in large quantities, and its use was recommended, or even mandatory, during hygiene and public health campaigns.

The first world war stopped this expansion. At the end of the war, there was a shortage of raw materials. Too few fats were available, and soap was becoming scarce. In 1916, in Germany, the first synthetic surfactant » appeared. This was the forerunner of what we now call synthetic surfactants. The Second World War forced even more innovation. New synthetic surfactants were developed. They were inexpensive, required few noble materials, were easy to manufacture

and assemble, and were mass-produced. In the 1950s, they replaced soap.

They are even preferred by consumers. It must be said that soap has become self-degrading. The industry has learned to separate the glycerin to sell it to other industries. Soap is over-industrialized, produced with low-end oils, and sold without glycerin. It dries out the skin. Ironically, synthetic surfactants are softened with the glycerin sold by the soap industry.

However, traditional soap making remains. It is discreet, reserved for purists, sometimes considered as folkloric or even old fashioned. It is also learning to defend itself. When industrialists decided to advertise and praise the merits of « soap without soap » (in short, synthetic surfactants), soap makers were up in arms. The war will be long but the name « soap without soap » will finally be withdrawn.

And, little by little, the traditional soap industry is attracting interest again. Shower gels are finally irritating, the smells and colors aggressive, advertising and marketing exhausting; saturation of bodies, minds and senses.

A new moment in the relationship to oneself, to hygiene and to the world.

Passionate about soap, clean and dirty? It’s this way:

- Françoise de Bonneville, Le livre du bain, 2004, Ed. Flammarion

- Alain Corbin, Le miasme et la jonquille. L’odorat et l’imaginaire social XVIIIème-XIXème siècles, 1986, Ed. lammarion

- Alessandro Giraudo, Nouvelles histoires extraordinaires des matières premières, 2017, Ed. François Bourin

- Roger Leblanc, Soap from prehistory to the 16th century, 2001, Ed. Pierann

- Georges Vigarello, Le propre et le sale. L’hygiène du corps depuis le Moyen-Âge, 1985, Ed. Seuil